Currently reading

Women / Men , by Paul Verlaine

Portrait of Verlaine by Edmond François Aman-Jean (c. 1892)

Intrigued after recently learning that Paul Verlaine (1844-1896) wrote and (partly) published sous le manteau poems that Stefan Zweig termed flatly and most disapprovingly "pornographic" in his little biography of the poet, I dug up a bilingual edition(*) of the most clandestine of these publications: Femmes, published in Brussels under a pseudonym at the end of 1890, and Hombres, which appeared posthumously in 1903/04.

First of all, what appeared at the turn of the 20th century to a very young Stefan Zweig to be pornographic strikes me instead as erotic, at most. Over a century later I'd say that pornographic art is primarily concerned with the curious mechanics of intercourse in its manifold varieties, whereas erotic art elides most of the hydraulics and focuses on the beauties of the human body, the initial mounting excitement and the pleasurable and appreciative sensations of the aftermath. I'd also claim that erotic art has no need of euphemisms, blurry focus or the many other kinds of prevarications I've witnessed over the years.(**)

4

4

2

2

Heritage and Challenge: The History and Theory of History

It often seems to me as if History was like a child's box of letters, with which we can spell any word we please. We have only to pick out such letters as we want, arrange them as we like, and say nothing about those which do not suit our purpose.

― James Anthony Froude

In the end the suspicion grows that all significant patterns ascribed to the past, in small matters as in large, are myths.

― Roland K. Stromberg

Heritage and Challenge: The History and Theory of History (1989), a revised and updated version of a book first published in 1971, consists of an overview of the history of Western historiography written by Roland N. Stromberg and then a taste of the theory of historiography written by Paul K. Conkin. Though at first glance such topics may seem to be a bit too self-referential, in my view such meta-historical considerations are just as important to readers of history as they should be to historians. The writing of history is so time and place dependent that some modern historians deny even the possibility of objective historiography. Stromberg briefly indicates how this temporal and spatial dependence actually manifested itself, and, in principle, Conkin equally briefly examines the conceptual and philosophical problems that arise in the very project of writing history. Stromberg provides what can only be regarded as an introduction to his topic; Conkin did not manage to do that for his.

At a little more than 100 pages Stromberg's contribution is a necessarily incomplete survey of the history of the writing of history since Herodotus in which the only non-Western historian mentioned is Ibn Khaldun. The extensive and culturally central tradition of history in China is dismissed in a sentence or two in a manner that sent my hackles rising. Stromberg's position apparently is that "history" is history as process, as evolution, and that this type of history did not arise until the end of the 18th century in Europe. Nonetheless, he starts with Herodotus and not with the 18th century. So why, again, is non-Western historiography excluded?

3

3

My Own Life , by David Hume

It is difficult for a man to speak long of himself without vanity; therefore, I shall be short. It may be thought an instance of vanity that I pretend at all to write my life; but this Narrative shall contain little more than the History of my Writings; as, indeed, almost all my life has been spent in literary pursuits and occupations.

This very short and charming overview of his life can be read here:

https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/h/hume/david/life-of-david-hume-esq-written-by-himself/

3

3

The People of the Sea , by Marc Elder

Marcel Tendron (1884-1933)

Deux hommes sur un rocher et voici la haine.

Marcel Tendron (Marc Elder his nom de plume) was a novelist, critic and art historian who spent most of his life in Nantes and its environs; not surprisingly then, it is reported that his many novels are all touched by the sea. In 1913 his fourth book, Le peuple de la mer (The People of the Sea) won the Prix Goncourt in the eleventh round as a compromise between the leading contenders, Le Grand Meaulnes and La maison blanche by a certain Léon Werth. A jury member later revealed that Du côté de chez Swann was briefly discussed, but Proust "n’avait pas fait acte de candidat."

So, what is there to say about a book that nobody remembers except Jean Echenoz?(*) Set just south of the Breton peninsula on the island of Noirmoutier at the turn of the 20th century, Le peuple de la mer presents a naturalistic picture of those who live from the sea - the fishermen, the shipwrights, the innkeepers, the women who work in the sardine canning factories and raise the children, merchants and customs agents. As is so often the case in small towns, the dominant emotion is envy fed by malicious gossip. But it doesn't stop at words on the isle of Noirmoutier; the book opens with an attempt to burn up a vessel under construction, an attempt providentially scuttled by the ship's anxious owner. So he names the ship Le Dépit des Envieux, and the gauntlet is cast.

4

4

Youth and Other Stories , by Mori Ogai

Mori Ogai (1862-1922)

Though not well known in the West, Mori Rintaro(*) is placed by experts here and in Japan at the apex of Meiji era (1868-1912) literature alongside his slightly younger contemporary, Natsume Soseki, and was deeply admired by writers as widely different as Nagai Kafu, Lu Xun and Mishima Yukio. He seems to have written with a scope, seriousness and range similar to such intellectuals as Jean-Paul Sartre, writing idiosyncratic novels, short stories, theoretical essays, poetry, criticism, biography and autobiography, polemic and pieces for the theater, as well as technical writings in medicine and public health, not to mention providing the first translations into Japanese of many of the best known European writers of the 19th century and editing an influential literary journal. And all of this was done while he was an army surgeon of increasingly wider professional influence, eventually to become the Surgeon General! Early in his career he was sent by his superiors for further study in Germany from 1884 till 1888, where he developed his thenceforth intense interest in European literature and philosophy. He began writing a little outside of his medical bailiwick after graduation from medical school, and the trickle eventually became a mighty river.

Such an unusual curriculum vitae suggests the possibility that Ogai might have a novel point of view that could provide insights not to be found among the ordinary crowd of literati, and such is indeed the case. But also his literary style is so unique that those seeking the usual pleasures are sometimes perplexed, if not rebuffed by his texts, particularly the late period shiden, strictly factual historical "fiction" in which none of the usual attempts at literary shaping are made. I expect to say something about those later texts after I finish reading the collection The Historical Fiction of Mori Ogai.

The primary focus here is on Youth and Other Stories (1994), a selection of his fiction starting at the beginning but not containing the historical fictions, with a secondary focus on Not a Song Like Any Other (2004), a selection of texts of various types, including fiction, theater pieces, essays, poetry and biography.(**) In these texts Ogai is not yet the majestically severe author of his final years, though he is most unmistakably his own man. There are too many pieces in these two volumes to examine separately, or even in groups, so I shall try to give some indication of the characteristics of his style and interests and then say a few words about one or two individual pieces.

5

5

The Skin , by Curzio Malaparte

Curzio Malaparte (1898-1957)

To win a war - everyone can do that, but not everyone is capable of losing one. - Curzio Malaparte

Curzio Malaparte, born Kurt Suckert to a German father and Italian mother, was a journalist and novelist who was a member of the Italian fascist party and took part in Mussolini's march on Rome in 1922. I don't know why he was initially a fascist, but he was too much of a free thinker to be one for long. He was kicked out of the party for his free thinking (and for lambasting both Hitler and Mussolini in various publications) and exiled on an island for five years; subsequently he was arrested and imprisoned multiple times. In between incarcerations he was an editor of a literary journal and of La Stampa for a time. During the Second World War he was a war correspondent for the Corriere della Sera. His most important novels, Kaputt (1944) and La pelle (1949), were both set in the war, the former on the Eastern Front and the latter during the invasion and occupation of Italy by the Allies.

I first read La pelle (The Skin, available in English translation) decades ago and was deeply affected by its merciless depiction of the misery and degradation of both the Italians and the occupying forces. After finishing John Horne Burns' outstanding satirical promenade through occupied North Africa and Naples, The Gallery, in which the same misery and degradation are among the primary focuses, I thought it was a good time to revisit La pelle, to see these portrayals of the same circumstances, one from an Italian and one from an American,(*) side by side.(**)

3

3

Paul Verlaine , by Stefan Zweig

Paul Verlaine and Arthur Rimbaud - detail of a painting by Henri Fantin-Latour (1872)

Il faut, voyez-vous, nous pardonner les choses. - Paul Verlaine

I chanced upon this little book while looking for a good biography of Paul Verlaine,(*) and though Stefan Zweig (1881-1942) apparently wrote Paul Verlaine when he was 23 years old, he was already in full possession of his prosodic powers and psychological insight. In a finely honed turn-of-the-century prose Zweig indicates in broad strokes the life of a man he presents as weak and easily influenced, though highly gifted and sensitive: from the perfect childhood through the beginnings of the fall when he was placed in a Parisian boarding house at the age of 14 so that he may study in a Parisian school, through the addiction to absinthe and the oh-so-brief career as a bureaucrat in the Parisian City Hall, through the arrival from the provinces of some stunningly new poems by a fifteen year old prodigy, through the obsessive, self-destructive relationship with said prodigy - which ended not with the famous gunshots and the two year incarceration in a Belgian jail, but with a tragicomic drunken brawl on the banks of the Neckar after Verlaine was released and tried to convert the young monster to Catholicism; Rimbaud was just about ready to say adieu to literature and to Europe - through the long years of artistic and physical decline after the apogee of the passionate poems of religious fervor written in the Belgian prison.

4

4

The Twelve and Other Poems , by Alexander Blok

Alexander Blok (1880-1921)

Alexander Blok, born into a well-to-do academic family,(*) is regarded by many experts as the most important Russian poet since Pushkin, and certainly the greats of the Silver Age of Russian poetry - Osip Mandelstam, Anna Akhmatova, Marina Tsvetaeva, Boris Pasternak - were influenced by his work. But to my mind, the children were greater than the father.

Blok was a man of Absolutes, a deeply romantic Symbolist even after the mystic experiences of the entity he called the Beautiful Lady faded away. Though he was an archetypal St. Petersburg intellectual, he shared Tolstoy's romantic view of rural, agricultural life, a life he dabbled in every summer on his family's estate, and damned the "artificial Hell" of St. Petersburg, where he nonetheless spent most of his life.

At first, Blok's lyric poetry was dedicated to his mystic pursuits and experiences, to that which is beyond time and to that part of love which he considered to be beyond time.(**) The tone is ecstatic, and his first book of poetry is full of this sort of thing. But he lost his contact with the Beautiful Lady and replaced her with a series of more human figures whom he recognized as leading him away from the Eternal, as "poisoning his soul", and also with "limitless Russia." But there are a few more appealing poems, poems flavored with Russian folklore and song, and poems which drop the high-flying symbols and spend a moment in actual life:

She came in from the frost

with her cheeks glowing,

and she filled the room

with a scent of air and perfume,

with her voice ringing

and her utterly work-shattering

chatter.

Immediately she dropped on the carpet

the fat slab of an art magazine

and suddenly it seemed

that in my generous room

was a shortage of space.

This was all a little annoying

not to say silly.

What's more, all at once she wanted

me to read Macbeth to her.

Hardly had we got to the 'earth's bubbles',

of which I cannot speak without emotion,

when I noticed that she too was moved

and staring out of the window.

And there was a big tabby cat

inching its way down the gable

in pursuit of some passionate pigeons.

I was annoyed most of all because

it was not us but the pigeons who were kissing

and that the times of Paolo and Francesca were over.

From around 1908 onward Blok tried to escape what he increasingly saw as the solipsism of his lyric poetry by turning to epic poetry (particularly the uncompleted "The Retribution" and the cycle “On the Field of Kulikovo”) and to drama. A few trips to Europe left him with the sense that Europe was only putrefied past.

Die, Florence, Judas, disappear

in the twilight of long ago!

In the hour of love and in the hour

of death I'll not remember you.

Oh, laugh at yourself today, Bella,

for your features have fallen in.

Death's rotten wrinkles disfigure

that once miraculous skin.

The motorcars snort in your lanes,

your houses fill me with disgust;

you have given yourself to the stains

of Europe's bilious yellow dust.

(The first stanzas of "Florence".)

When the February Revolution arrived, Blok welcomed it, writing his most famous poem, "The Twelve," in January, 1918. What an unusual creation it is!

Some twenty pages long, it mixes scraps of direct speech, songs and prayers with onomatopoetic representations of firing rifles and machine guns to relate a strange story of twelve (the number is not arbitrary) Red Guards who are searching through a blizzard in St. Petersburg for a young woman who was spirited away by another young man in a cab. Finally finding them, the Red Guards fire a salvo to which only the young woman falls victim. After a brief lament the young men bluster and threaten the city with mayhem. And then the poem changes as the soldiers continue marching into the blizzard:

Abusing God's name as they go,

all twelve march onward into snow...

prepared for anything,

regretting nothing...

Their rifles at the ready

for the unseen enemy

in back streets, side roads

where only snow explodes

its shrapnel, and through quag-

mire drifts where the boots drag...

before their eyes

throbs a red flag.

Left, right,

the echo replies.

Keep your eyes skinned

lest the enemy strike!

It goes on like this to my increasing consternation until the poem closes with:

....So they march with sovereign tread...

Behind them limps the hungry dog,

and wrapped in wild snow at their head

carrying a blood-red flag -

soft-footed where the blizzard swirls,

invulnerable where the bullets crossed -

crowned with a crown of snowflake pearls,

a flowery diadem of frost,

ahead of them goes Jesus Christ.

(!!!) Trotsky is reported to have said with disgust: “What was the point in climbing our mountain in order to erect a medieval shrine on the top?” I should mention that Blok rejected Christianity for his particular flavor of mysticism. Asked to explain, Blok commented, “If you look into the snow along that road, you will see Jesus Christ.” OK then!

I expect it was not the rather confused sentiments of the poem which allowed it to last, but the remarkable mixture of voices and styles in which they are expressed, particularly remarkable in a Russian poetic tradition which was still in thrall to the 19th century. After writing "The Twelve" and the nearly equally curious "The Scythians," in which Blok presents the Russians as the bulwark of the West against the East, he stopped writing poetry and turned entirely to his efforts in the theater. Nonetheless, his musical and highly rhythmic idiom became one of the ingredients in the formation of the next, and truly great generation of Russian poets. In my humble and very incompletely informed opinion...

The Twelve and Other Poems (1970) is a collection of translations of fifty poems put together by the team of John Stallworthy and Peter France. They made a real effort to reflect the poetic nature of Blok's work, and write in their introduction that in the ever present translators' fidelity or beauty question they came down firmly on the side of beauty. As I now incline to think that Blok's greatness lies less in his ideas than in his technique, I think that Stallworthy/France made the right decision here.

(*) His grandfather was the Rector of St. Petersburg's university and his father was a law professor at the University of Warsaw.

(**) According to his biographer, Avril Pyman, Blok felt that love was eternal and sex was demonic, carrying this to the point that his was a white marriage until his wife finally succeeded in seducing him in the second year of their marriage.(!) She was too inexperienced for that to last, because he had already acquired a taste for the "demonic" and frequented prostitutes. (He died at the age of 40 of an unspecified venereal disease which was surely syphilis.) She eventually turned to Andrei Bely for solace, presenting Blok with a son he pretended was his own.

4

4

Stone in a Landslide , by Maria Barbal

Ye are the salt of the earth: but if the salt have lost its savor, wherewith shall it be salted? it is thenceforth good for nothing, but to be cast out and trodden under foot of men.

- Matthew, 5:13

The phrase "salt of the earth" is used in so many ways, and a quick web search yields little consensus. I personally use it to mean "a decent, dependable, unpretentious person," and it is in this sense that the narrator, nicknamed Conxa, of the novella Pedra de tartera (2008; translated into English as Stone in a Landslide) by the Catalan author, Maria Barbal (b. 1949), is the salt of the earth.

With quick, calm strokes Barbal sketches the life of a girl in the Catalan mountains in the early 20th century - the hard work, nearly inexistent education, early marriage and quick succession of births, the passing of generations. In other words, the hardscrabble life of the overwhelming majority of humanity until quite recently. As if the struggle with Nature were not hard enough, the magic word "republic" reaches even the miniscule mountain village where Conxa lives with her growing brood. Then History arrives, and she isn't kind.

4

4

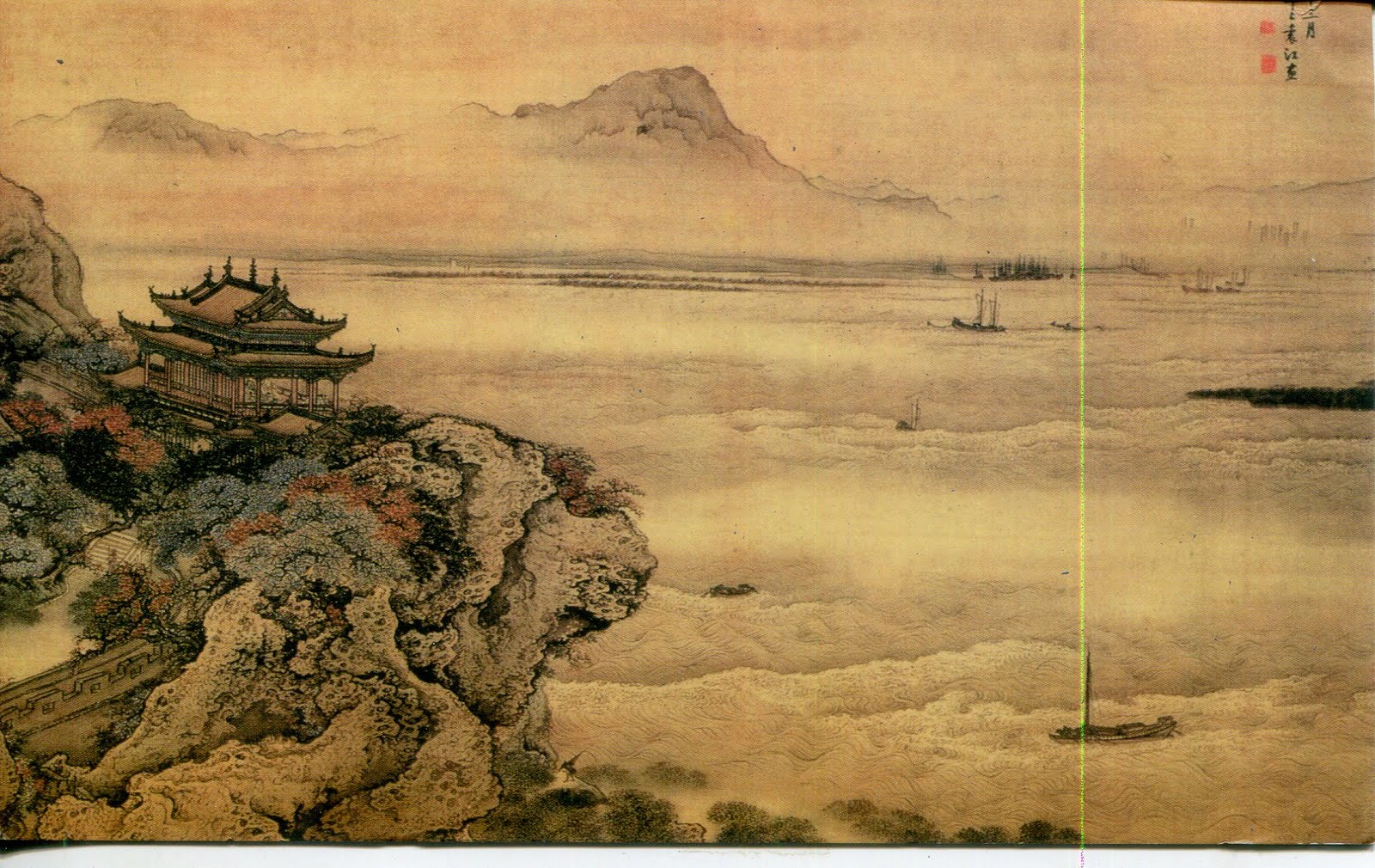

Hojoki , by Kamo no Chomei

- Calligraphy by Hon'ami Kōetsu (1558–1637), Underpainting attributed to Tawaraya Sōtatsu (died ca. 1640), Poem by Kamo no Chomei (ca. 1154 – 1216)

If we follow the ways of the world, things are hard for us; if we refuse to follow them, we appear to have gone mad.

As I understand it, Hojoki is read by every Japanese student in school and had a great influence on much that was subsequently written in Japanese. It is one of the key texts of the Japanese culture. Written by Kamo no Chomei in 1212 during the collapse of the Heian dynasty, it is a poetically dense text, whether it is rendered in free verse, as is done in this book, or into prose, as is done by Donald Keene in his pioneering Anthology of Japanese Literature .

An earlier reviewer wrote "However, it seems inadequate - lacking in richness of human experience..." I beg to differ. In a highly distilled poetic language Chomei describes the destruction of one third of Kyoto by a ravaging fire in 1177 with the concomitant horrible deaths; then a monstrous tornado tore a swath 2 kilometers long through the city in 1180. Shortly thereafter the Emperor decided to move the capital, creating huge problems for the populace, totally uprooting their lives; six months later the Emperor moved the capital back to Kyoto! A two year long famine followed in 1181-1182, and Chomei evokes the terrible consequences and the altruistic acts of some of the inhabitants. As if that weren't enough, a great earthquake leveled the city in 1185... These are indicated in brief, sharp strokes of the brush, not dwelt upon in gory detail as would be done now.

Chomei, who converted to Buddhism, supplements these clearly drawn illustrations of the precariousness of life and property with further examples of the problems of attachment (to property, ambition, social status, loved ones, life). After many disappointments and losses, Chomei "withdraws from the world," builds and lives in a series of wooden huts in the countryside; he lovingly describes his simple life there. Some lines from this section:

Then in winter -

snow!

It settles

just like human sin

and melts,

in atonement.

He plays music, writes, watches Nature, shares long walks with a 10 year old boy who occasionally visits, remembers friends and family, gathers from Nature the necessities to satisfy his very modest food and clothing needs. But he is aware that he is now attached to his very simple life and reproaches himself for not being as mindful as some figures of Buddhist legend. He is stuck in the quandary inherent in every absolute ideal:

To these questions of mind,

there is no answer.

So now

I use my impure tongue

to offer a few prayers

to Amida and then

silence.

(Amida is the Buddha of comprehensive love.)

OK, Hojoki is not War and Peace or A Tale of Two Cities ; it is 15 pages long in Keene's prose version. But I rather doubt that any 15 pages in those books are as dense in human experience as Hojoki is! Be that as it may, I find this to be a rich and moving text to which I often return. My gratitude is due to the translators of this free verse version for providing another view of the text for those of us with no Japanese. I have the feeling that I will re-read this more often than Keene's fine prose version.

4

4

The Nobility of Failure , by Ivan Morris

- Utagawa Toyokuni (1769 - 1825)

As Ivan Morris (1925-1976) is best known for his translations and interpretations of the hyper-aestheticized culture of the Japanese imperial court of the Heian era (794-1185), one may well be startled to learn that the last book he published before his regrettably premature death was an examination of the role of failed heroes throughout Japanese history. In fact, he tells us in his preface to The Nobility of Failure: Tragic Heroes in the History of Japan (1975) that Mishima Yukio complained to him that his focus on the Heian period court ignored Japan's long martial history and left out crucial aspects of the Japanese character. Morris took this to heart and wrote a 500 page response examining the lives and deaths of nine famous Japanese men of action which closes with a chapter about the kamikaze pilots of the Second World War. Morris chose to focus on tragic heroes, because they play a role in Japanese culture which has no real counterpart in the West.(*)

Perhaps when searching for a Western analogue one might think of Admiral Nelson being struck down just as his greatest victory was revealing itself, but to die under such circumstances would not be viewed as tragic by a samurai; on the contrary, Nelson's fate would be the most hotly desired goal of any samurai. The Spartans who fell at Thermopylae were defeated, but they slowed and weakened the Persians so that the rest of Greece could finish the job on the plain of Marathon; moreover, they shared the samurai's estimation of honorable death in battle. Not even the men who died at the Alamo - most of whom did not share the death-dedicated values of the Spartans and samurai - are tragic heroes in the sense at hand because their lengthy resistance and ultimate defeat assured the subsequent defeat of the Mexican forces.

No, a tragic hero in the sense considered here is one who dies not only in defeat, but the more abject, ineluctable and obviously vain (from our point of view) the defeat, the greater the tragic hero is. As Morris mentions, just such heroes were the men Mishima most admired, and it is now clear to me that Mishima was not trying to spur an uprising when he addressed that band of soldiers from that balcony. He knew perfectly well that they were not going to do anything, and, even if they did, they would accomplish nothing against the power of the Japanese state. No, he joined the men he most admired by dying in the most pointless defeat he could arrange. After speaking his bold and (by his lights) noble words and viewing the probable mix of consternation, fear and disbelief in his audience's faces, he withdrew to a small coterie of his fellow believers and committed seppuku (harakiri) surely the most painful way to kill oneself (except possibly burning oneself alive).

5

5

Less Than One - Selected Essays , by Joseph Brodsky

Man is what he reads, and poets even more so.

Joseph Brodsky, born Iosif Aleksandrovich Brodsky (1940-1996), was, as the name suggests, a Russian of Jewish descent, who emigrated to the USA in 1972. It is never a trivial matter to leave one's own country behind, but for a poet emigration to another language must be particularly wrenching. Nonetheless, Brodsky acclimated himself to the language of his new home well enough that he also became an accomplished poet in English, serving as the Poet Laureate of the United States in 1991 and 1992. But the topic of my discussion today is not Brodsky's poetry, rather it is his collection of essays, Less Than One (1986).

Less Than One collects eighteen pieces of various origin and of necessarily varying interest, including an extended obituary of Nadezhda Mandelstam, a lecture from a literature course and a commencement address at Williams College. But most are genuine, very perceptive essays focused on poets and poetry. That fact will surely constrain the prospective audience in our benighted times, but for me it was a sweet lure taking me happily from one essay to the next.

4

4

The Journal of Wu Yu-bi

Dai Jin (Tai Chin, 1388-1462)

The noble person tends to his own situation in life. How could he take what comes from the outside world as true honor or disgrace?

- Wu Yu-bi

Is philosophy a body of knowledge or a transformative way of life?

I know the answer most academic philosophers would now give, but it was not always that way. I've touched upon this matter before in my review of Qu'est ce que la philosophie antique?, in which Pierre Hadot made the case that there was an entire tradition of Greco-Roman philosophy concerned with transforming the philosopher into a sage, for whom philosophy was a way of life and not merely a body of knowledge to be acquired either for its own sake or for another purpose (such as becoming a more persuasive and influential politician or lawyer) or a set of intellectually interesting abstract questions about which one could pleasantly speculate. In Pursuits of Wisdom John M. Cooper wrote a rejoinder which by my lights set up straw men and knocked them down again. Though interesting in the portions of the book which provide an overview of the various schools of Greco-Roman philosophy, as a polemic it failed to convince me. Having read in the meanwhile the letters of Seneca and what is left of the writings of Epicurus and Epictetus, not to mention the Socratic tradition as represented in Plato's dialogues, the existence of a tradition of philosophia that included a transformation of the individual with the goal of becoming a sage is certain. That there were other, parallel traditions is equally certain.

However, in China, at least until very recently, philosophy was concerned with the transformation of the individual, whether it was labelled Taoist, Buddhist or Confucian.(*) The entire state examination system, put in place already during the Han dynasty, made neither science nor the management of large bureaucracies part of its curriculum, but rather poetry, history and philosophy were the focus of its students, in the expectation that they would become more moral, more in tune with the lawful harmony of Heaven and Earth through their study of these.(**) This goes well beyond matters of mere knowledge.

5

5

Studies in Chinese Philosophy , by A.C. Graham

I was previously familiar with the Welsh sinologist A.C. Graham (1919-1991) through his excellent translations in Poems of the Late Tang, but it turns out that he was much more the philosopher than poet. Graham wrote a few original books on philosophical matters, as well as a number of books that closely examine classic Chinese philosophical thought. Studies in Chinese Philosophy and Philosophical Literature (1986) is a collection of essays Graham published in academic journals for specialists but which I, a non-sinologist quite incapable of reading Chinese, found riveting. Yes, riveting!

Just as I read about other cultures for their own intrinsic interest, I am also interested in the critical reflections these throw back on my own culture. Even the as yet superficial familiarity with aspects of Chinese philosophy I have acquired to date has opened my eyes to tacit assumptions made in Western thought. And this is not an unusual phenomenon; as Graham writes in his Introduction:

It hardly needs saying that a Westerner can never be as fully at home in the traditional Chinese world-picture as in his own. However far he penetrates he never ceases to impose Western presuppositions, and from time to time awaken to one of them with an astonished "How could I have failed to see that?". ... Later, as he finds his bearings, he comes to appreciate that if in his own tradition there seem to be arguments with no missing links or grounds it is because he and the philosopher ask the same questions from the same unspoken assumptions, and that in Chinese arguments too the gaps fill in when the questions and assumptions are rightly identified. ... One learns to distrust any interpretation which credits the Chinese with too obvious a fallacy. The concepts are different, perhaps even the categories behind them, but the implicit logic is the same.

4

4

Zorba the Greek , by Nikos Kazantzakis

Woe to him who cannot free himself from Buddhas, Gods, Motherlands and Ideas.

- Nikos Kazantzakis

Though this book hardly needs yet another review, I felt an overwhelming urge to pick up the pen, errrrh, slide out the keyboard, for Kazantzakis has wonderfully demonstrated the old truth: life is pitiless, terrible and beautiful, and we have no owner's manual.

Everyone has heard of Nikos Kazantzakis' (1883-1957) Zorba the Greek,(*) due largely, I suspect, to the well known movie Hollywood made of the book. Unfortunately, such a circumstance is well suited to cause me to make a wide detour around the book. Sometimes such a prejudice leads one into error, and this is such an instance.

5

5

History of the Late Roman Empire, Part II, by Ammianus Marcellinus

Emperor Julian

Once again, the Roman Empire in the 4th century; this time as seen by a contemporary witness.

In this review I report on the second of four volumes of the German edition of Ammianus Marcellinus' history of the late Roman Empire I chose to read. For general background, information about English translations, and a discussion of the first volume, please see Römische Geschichte, Erster Teil.

3. Volume 2: Books 18-21

Book 17 ended ominously with the Persian King of Kings' demand that the Romans return Armenia and Mesopotamia to Persian suzerainty. That wasn't going to happen without a fight. Book 18 opens with further successful military actions of Caesar Julian against the Alemannic tribes east of the Rhine and with his efforts to reintroduce a just rule of law in Gaul and to rebuild and reprovision the cities and fortifications along the Rhine which had been destroyed, but most of Books 18 and 19 provide a first hand report of one season of the war with the Persians. For Ammianus was on the staff of the Roman supreme commander in the East, Ursicinus, and gives us in these Books one of his most gripping, detailed and extensive "I-passages," as I shall briefly explain below.

Urged on by a Roman deserter, the Persian Shah, Sapor, sent a large army across the Tigris into Roman territory, an army that at least partially disintegrated into roving bands of plunderers. For complicated reasons Ursicinus (who had just been relieved of command through an intrigue at Constantius' court) and Ammianus rode into one of these bands unsuspectingly and then had to ride for their lives, having the kind of adventures told in the Flashman series (though these men were definitely not cowards). With too many side stories(*) to tell here, let me focus on the following story concerning events that occurred after the Romans withdrew to the west bank of the Euphrates.

4

4