Currently reading

The Tales of Ise

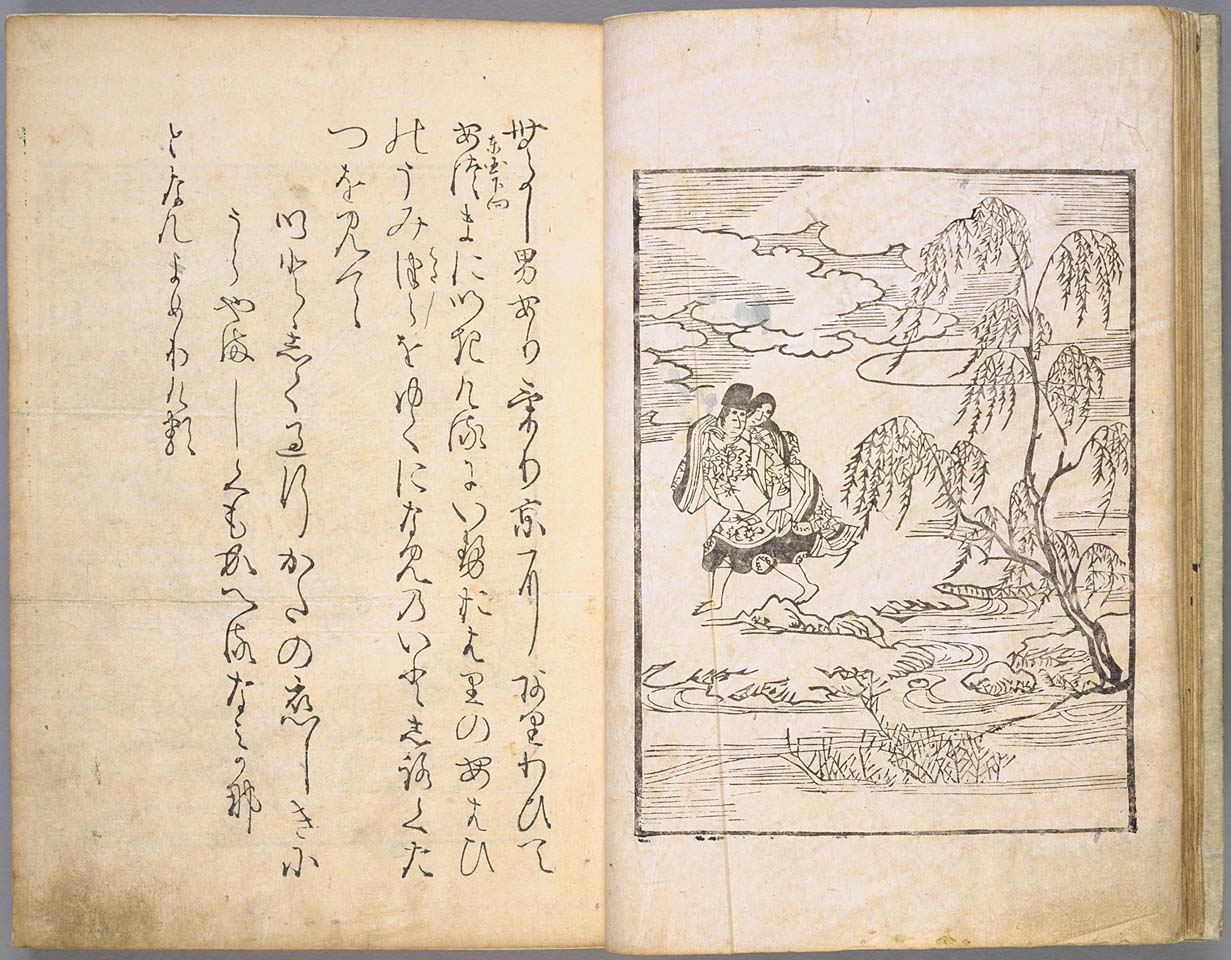

Two pages of Ise monogatari in a lovely edition from the early Tokugawa era (1608).

Nota bene: I have combined the reviews of two translations/commentaries of Ise monogatari into one. If you've read the one review, then you've read the other.

Some of Japan's oldest texts have been holding me enthralled. After the life and poetry of Sugawara no Michizane (845-903), it is now the Ise monogatari (The Tales of Ise) that have connected with me through the intervening centuries. Though the experts are still arguing about who wrote it and when (and their task is not simplified by the fact that it had a long genesis with multiple stages and later editors felt entitled to make interpolations), it would appear that Ise assumed the essentials of its present form somewhere between 905 and 951.(*) The author/compiler of that text is not known, but it is known that (1) approximately one-third of the poems in Ise are the work of Ariwara no Narihira (825-880) and (2) other portions were written after Narihira's death.

Narihira, the grandson of an emperor through a secondary wife, must have been quite a character. Praised for his manly beauty and for his mastery of poetry in Japanese, he somehow managed to avoid the then standard obligation at the Japanese court to be expert in Chinese language and literature in an age when the writing of Japanese verse was associated with women and love poems. In fact, in the Sandai Jitsuroku (True Annals of Three Reigns) he is described as follows:

In appearance elegant and comely,

his self-indulgence notwithstanding,

seriously wanting in Chinese learning,

a fine craftsman of the native poetry.(**)

As with Lady Murasaki's Genji monogatari (The Tale of Genji, ca. 1008), we are in a fix when we try to classify Ise. So why bother? What is this obsession with round pegs and square holes? Instead of classifying Ise, let's look at it carefully. Genji is episodic and, for readers whose taste was formed by the Western novelistic canon, rather elliptic in certain respects and somewhat narrow in focus. But compared to Ise, Genji is prolix and markedly expansive.

The most widely disseminated versions of Ise consist of 125 extremely short episodes (dan) composed of brief prose passages linking a few poems within each episode. There is a recurring male "character" (who, actually, cannot always be the same person) and much of his activity is locating, wooing and seducing women, though the last step is not always successful, resulting in a heartfelt lament. Frustrated desire not infrequently results in abduction. The poems, which can hardly be said to advance any plot, are evocatively indirect, focusing on little details bespeaking states of emotion. The indirection is so extreme that commentaries attempting to interpret Ise for befuddled readers sprang up almost immediately, resulting in a huge, convoluted and mutually contradictory tradition(***) which, from what little I have seen of it, is often more revealing of the individual commentator's attitudes and times than it is of the text being interpreted. (No surprise there.) The lack of clarity is further increased when the later interpolations actually contradict the passages from the earlier archaeological levels of the text. This text was not written to be understood but to be felt. It is an expression of early Japanese attitudes and aesthetics and has been influential to the present: every educated Japanese from the Muromachi period on had to read the Kokinshu, Genji monogatari and Ise monogatari, despite the somewhat questionable sexual morality of the latter two (from the point of view of the official morality).(4*)

One can see that Ise and Genji were written nearly a century apart: the court societies described by Genji and Ise differ noticeably - in Ise the Fujiwara(5*) were rising but still had competitors (including the emperors themselves), in Genji the Fujiwara were in control; in Ise the court aristocracy was not yet completely disconnected from the Japanese people, in Genji they were in their own never-neverland; the nebulous mysticism and use of geomancy, astrology, etc. of the courtiers in Genji is absent in Ise; the pioneer spirit of the 8th century Japanese aristocracy is weakened but still present in Ise, while in Genji they have arrived at a hyper-aestheticized state which I hesitate to characterize in a few words.

In an attempt to triangulate the Japanese text behind two well regarded English translations, I read The Tales of Ise (1972) by H. Jay Harris and The Ise Stories (2010) by Joshua S. Mostow and Royall Tyler. Both Harris and Mostow/Tyler maintain the original 5-7-5-7-7 syllabic line count when translating the poetry, but in most other respects diverge strongly. Consider the first poem of the first episode:

Harris:

Fields of Kasuga

with whose tender, purple shoots

this gown has been dyed:

This confusion of my heart

whose boundaries no man knows...

Mostow/Tyler:

Young murasaki

sprung from Kasuga meadows,

you impress my cloak

with such Shinobu tangles,

they will never come undone.

They are in little more agreement about the prose passages. Both books offer extensive notes and reproductions of Tokugawa era illustrations of Ise monogatari from the same 1608 edition (see top). The notes provided by Mostow/Tyler also give a taste of the Japanese commentaries to Ise. I found that the notes of Harris, resp. Mostow/Tyler hardly overlapped and both were useful.

(*) Nonetheless, scholars believe that episodes were added at the beginning of the 11th century, and smaller changes were being made to various versions as late as the 16th century. All the oldest manuscripts have been lost, and there is no single, canonical Ise monogatari.

(**) Apparently, some scholars now prefer to interpret the third line as "not the conscientious type."

(***) Eloquently indicative is the following quote from Mostow/Tyler's commentary on dan 4: The meaning of the poem in this episode has been debated for centuries, the result being a numbing number of interpretations.

(4*) For example, though the Meiji ideologues condemned the "loose morals," they projected found political grounds to approve of Ise.

(5*) The Fujiwara family had increased its power slowly and carefully from the beginnings of the Heian era through a policy of marrying their daughters into the royal family, placing the youngest resultant princes upon the throne and ruling the country as regents.

2

2