Currently reading

Crabwalk , by Günter Grass

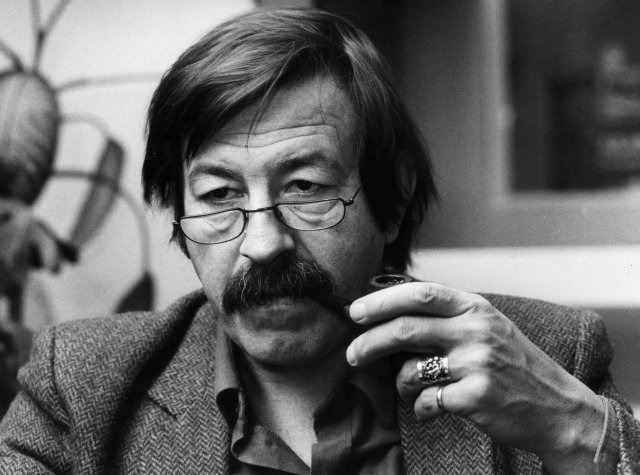

Günter Grass' (b. 1927) Im Krebsgang appeared in 2002, a late work, but one of the best Grass ever wrote.

The "incident" at the center of this book is not well known - I learned about it only recently in the pages of Max Hastings' excellent Armageddon, The Battle for Germany, 1944-1945. In late January, 1945, the six million man Red Army had finally pushed the Axis armies into Germany, and looting, burning, rape and murder were the payback for years of the same committed by the Axis powers in the Soviet Union. German civilians were desperate to escape to the relative safety of the region soon to be under the boot of the Allies. On January 30 a former cruise ship, the Wilhelm Gustloff, designed for a complement of 1,900, was packed with an estimated 8,000-10,000 persons (civilians and some soldiers, many severely wounded), including some 4,500 children, and set course westward in the frigid Baltic Sea ( -18 degrees Celsius were measured; an icebreaker had to open a passage in the Danzig Bay). A Russian submarine happened upon the vessel and sank it with a loss of all but 949 known survivors (according to Hastings; 1,239 according to Grass), making this the greatest maritime disaster in history. (A week later the same submarine sank another such refugee ship, from which only 300 of a complement of 3,000 survived.)

Grass was born in Danzig, a few miles from the port from which the Wilhelm Gustloff began its last voyage. He may well have known some of the people who disappeared into the Baltic's deathly cold waters. So, how did he choose to write about this horrific incident?

Complexly, with many layers. The narrator is a mediocre journalist whose mother was aboard the Wilhelm Gustloff that fateful evening; he was born that night in the ship that rescued her. He dances around the central incident with fascinated horror and repulsion, approaching it, touching it, and then hastening away. To avoid addressing it he tells the story of his entire family(*) up till the present, as well as those of three outsiders: the Nazi functionary after whom the ship was named, the Jewish student who assassinated him in Switzerland, and the captain of the Soviet submarine that fired three torpedoes into the overfilled ship. He also tells the story of his research about the incident, including the close inspection of Nazi-friendly websites(**), as well as the entire life story of the Wilhelm Gustloff. These are told in a complex simultaneous mixture of all of these and still more elements, jumping about through time and space.

Grass himself appears in the book as an old and "tired" writer who encourages the narrator to finally give expression to the suffering of the east Prussians, instead of leaving it up to the right wing revanchists. Now and again, Grass gives him advice how to proceed.

When the narrator finally brings himself to describe the actual sinking, he tries to remain as reserved, as factual as possible, relying on the reports of the survivors, of the complement of the single accompanying German ship, and of the sailors of the Russian submarine. I won't say anything more about it.

However, 1/4 of the book still remains, because as moving as the history surrounding and the story of the sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff is, in the narration of his family's history and of the brown websites Grass has not merely allowed his narrator to avoid describing the traumatic incident but has been, in a completely non-abstract manner, ruminating about mankind's relation to history - what individuals don't know, what they think they know, what they are willing to "modify" or assume, what they are willing to do in the name of their understanding of history. In this final quarter of the text another surprise emerges; another, smaller tragedy occurs which further extends and deepens the book. I won't spoil any surprises.

Grass' prose is neither flashy nor brilliant in this text (though I enjoyed the Danziger dialect the narrator's mother always speaks). The art in this book is manifested in the tightly woven mesh of so many distinct threads. I'm simply amazed at how much Grass could fit into a 216 page text without seeming to be an overloaded information dump. On the contrary, Im Krebsgang is a rich, harrowing and moving book. It is in every respect the fourth volume of a Danzig tritetralogy, the primary reason why Grass received the Nobel Prize.

(*) His free spirited mother, Tulla Pokriefke, also made an appearance in Grass' Katz und Maus (Cat and Mouse), the second book in Grass' Danzig Trilogy.

(**) One of which supplied him with a most unpleasant surprise.

7

7