Currently reading

An Island Archaeology of the Early Cyclades , by Cyprian Broodbank

The real life, and the history, of the early Cycladic civilization is still almost blank and therefore perplexing.

- Emily Vermeule, Greece in the Bronze Age (1964)

[Nota bene: I'm combining the reviews of two books into one and using it for both books. So if you read one, you've read them both.]

I well recall my amazement and fascination as a young man learning to love modern art when I first saw images of marble figurines made by the late neolithic and early Bronze Age artists on the Aegean islands we now call the Cyclades. For in their perfect simplicity and distillation of the essential these pieces had seemingly anticipated important aspects of 20th century European art. I knew then that artists such as Picasso, Moore, Modigliani and Brancusi recognized and were influenced by these early artists' attempts, partially from necessity and surely also at least partially from a deep artistic need, to find the perfect signe of the objects they were representing. But at the time little was available to provide a firmer grasp of the civilization that had brought forth these pieces.

In the meantime I have seen a significant number of these enigmatic but highly evocative objects in New York, Paris, Berlin, Athens and elsewhere, but I had to make do with the very scanty context usually provided in museums. In the midst of my project to try to grasp the full span of Greek culture, from the beginnings to the present, I had to satisfy my old longing to learn about the Cycladic culture. The relatively recent An Island Archaeology of the Early Cyclades (2000) by Cyprian Broodbank and the exhibition catalog Silent Witnesses: Early Cycladic Art of the Third Millennium B.C. (2002) partially assuaged this thirst.(*) Unfortunately, as Broodbank freely admits, Emily Vermeule's words above still ring true.

As no written records remain from the Cycladic culture (they probably never existed) nor, apparently, anything about the Cycladic culture in the written records of the peoples with whom they were in contact,(**) one is limited to the archaeological record. Broodbank's book, based upon his Ph.D. dissertation, is a synthesis of all of the available archaeological knowledge and provides an overview of Cycladic culture from its origins in the 5th millennium BCE till its interaction with the Minoan and Mycenaean cultures in the 2nd millennium BCE.

"The Cyclades" refers to the several hundred islands between Crete and Athens of which the most well known are probably Delos, Naxos, Paros, Mykonos, Andros and Thera (Santorini). Altogether they constitute a surface area of just 2,572 square kilometers (according to an essay in Silent Witnesses). Dry and rocky, they wouldn't seem to be particularly appealing places to live, then. But at least some of them have been inhabited since the end of the 6th millennium BCE. Currently only 34 have inhabitants (ibidem) and these are largely held in place through subsidies and tourism.

The first point to emphasize is that not only did Cycladic culture evolve significantly over the millennia of its existence, but that, as is the wont of island societies, cultural details can vary markedly on islands separated by only tens of miles. So already the taxonomy of Cycladic culture is complicated, and I won't even try to make a summary here. You'll find that in Broodbank's book.

Most of the striking pieces pictured here and collected in museums date from the Early Bronze Age, c. 3200 - 2000 BCE. The Cycladic sculptors preferred forming their thoughts in marble; even during the Archaic and Classical period when on the Greek mainland sculptures were made in bronze, the islanders stayed with marble. They started early and have maintained an affinity to sculpture till the present. According to one of the essays in Silent Witnesses, most of the Greek sculptors active today originated in the Cyclades.

Just like the European aesthetes in the 18th century when the "purity" of classic Greek sculpture came into vogue, the modernist painters and sculptors misperceived the original intentions of the Cycladic pieces, because residue analysis and ultraviolet reflectography have revealed that most of the Cycladic figurines were painted with faces, hair, and skin designs of the type still to be seen on North African tribespeople. But I, too, prefer the more abstract present state of the pieces.

Given the scanty evidence at hand, one can only speculate about the thought and beliefs of these people. My old desire to understand the source of these pieces is still unsatisfied. But it is certainly suggestive that no temples have been found and that all of their sculpture represents human beings, some almost lifesize - the Cycladic people appear to have been very anthropocentric and to have maintained a modest, human scale in their habitations and settlements. The fishermen, farmers, husbanders and artists of the Cyclades seem to have been people after my own heart...

I'll close with a few more suggestive images.

Yes, Yes, YES!

Evidently, they had chairs, harps (as well as panpipes and flutes) and music to sweeten their lives:(***)

and many kinds of pottery:

The centerpiece is rather more ornate than is typical. The pottery usually mirrors the same aesthetic values of simplicity, symmetry and plasticity apparent in the sculpture. Besides using fired clay, they also carved vessels, containers and other implements from marble.

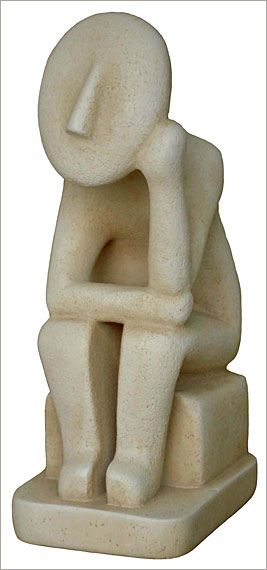

And millennia before Rodin, they had a Thinker:

This is actually a modern reproduction of the Cycladic original, for which I could find no images online.

I still love these.

(*) The exhibition catalogue Silent Witnesses: Early Cycladic Art of the Third Millennium B.C. (2002) offers informative, less technical, brief essays about the archaeological sites and evidence and some details about a few of the Cycladic pieces, as well as relatively high quality images of Cycladic sculpture, pottery and other artefacts. Broodbank's book is wide ranging, richly detailed and scholarly; it includes a critical analysis of current approaches to island archaeology in general in Chapter 1 and to Cycladic archaeology in particular in Chapter 2, sets the Cycladic culture into a large context of developing Mediterranean and Near Eastern cultures, and provides a lengthy bibliography.

(**) Throughout coastal Greece, Crete and the eastern Aegean.

(***) There is also a rock carving of three men dancing in a circle.

4

4