Currently reading

Poèmes saturniens , by Paul Verlaine

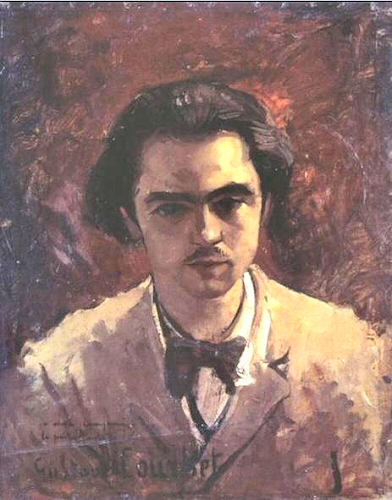

A young Paul Verlaine, painted by Gustave Courbet c. 1871

[4 stars]

When his first book of verses, Poèmes saturniens, appeared in 1866 at his own cost, Paul Verlaine was 22 years old and had been writing poetry since his early teens. He was still under the influence of the Parnassians like Charles Marie René Leconte de Lisle and Théophile Gautier,(*) who were proponents of l'art pour l'art - art for art's sake - and inveighed against les passionists. Many of the poems in Poèmes saturniens had been published in journals either edited by or sympathetic to the Parnassians. But Verlaine was already deeply engaged with the poetry of Charles Baudelaire, a poet with a singular style and vision whom many have tried to copy without equalling, and he was already freeing himself from the Parnassian grip.

At 22 Verlaine was still the very comfortable son of a well-to-do family and had no idea of the heights and depths of the life that lay before him. He had money in his pocket and was a recognized apprentice in Paris' literary world. And he had no emotional ties, except to his mother. All of that was soon to change, but this story will be told in other reviews.

Through his entire career Verlaine was more the musician than the painter,(**) and much more the poet than the thinker. He was also the sort of poet I appreciated much more when I was a "tormented" young man than I do now [blend in Voltaire's serene smile] - a highly sensitive and self-obsessed writer for whom any glances away from his bellybutton towards the outside world were just opportunities to project his moods and concerns onto a wider screen.

Nonetheless, nonetheless... His music, his floating moods still reach me.

Though there are some flat copies and pastiches in Poèmes saturniens, there are also some fine pieces where he has already found the waters of his poetic source. And because his music and moods are inseparable from his language, I won't offer any translations(***), with apologies to those not well versed in French. I also won't enter into technicalities, but in this text Verlaine artfully adapts a metric scheme used primarily in the 16th century in France (vers impair) to his purposes. For example, consider this little poem written in lines of five syllables.

Marine

L'océan sonore

Palpite sous l'oeil

De la lune en deuil

Et palpite encore,

Tandis qu'un éclair

Brutal et sinistre

Fend le ciel de bistre

D'un long zigzag clair,

Et que chaque lame,

En bonds convulsifs

Parmi les récifs,

Va, vient, luit et clame,

Et qu'au firmament,

Où l'ouragan erre

Rugit le tonnerre

Formidablement.

Poèmes saturniens contains many sonnets, of which the following anti-romantic poem echoing Baudelaire and Gautier and striking a pose that is not quite credible for a 22 year old fils de bourgeois is a technically fine example.

L'Angoisse

Nature, rien de toi ne m'émeut, ni les champs

Nourriciers, ni l'écho vermeil des pastorales

Siciliennes, ni les pompes aurorales,

Ni la solennité dolente des couchants.

Je ris de l'Art, je ris de l'Homme aussi, des chants,

Des vers, des temples grecs et des tours en spirales

Qu'étirent dans le ciel vide les cathédrales,

Et je vois du même oeil les bons et les méchants.

Je ne crois pas en Dieu, j'abjure et je renie

Toute pensée, et quant à la vieille ironie,

L'Amour, je voudrais bien qu'on ne m'en parlât plus.

Lasse de vivre, ayant peur de mourir, pareille

Au brick perdu jouet du flux et du reflux,

Mon âme pour d'affreux naufrages appareille.

Finally, in the next poem Verlaine employs a structure I've not seen before with some off-rhymes (the "rhyme" automne/monotone he certainly cribbed from Baudelaire). The ancient Chinese always read their poetry aloud, even when alone. This poem must be read aloud. One final aside: The first stanza was the code read over the BBC to signal to the French resistance that the invasion of Normandy was underway.

Chanson d'Automne

Les sanglots longs

Des violons

De l'automne

Blessent mon coeur

D'une langueur

Monotone.

Tout suffocant

Et blême, quand

Sonne l'heure,

Je me souviens

Des jours anciens

Et je pleure;

Et je m'en vais

Au vent mauvais

Qui m'emporte

Deçà, delà,

Pareil à la

Feuille morte.

Despite the lack of sales and critical resonance, the career of the man later to be declared "le prince des poètes" was well and truly launched.

(*) But Gautier was not "just" a Parnassian.

(**) Oh, how composers love to set his poems!

(***) Most of his poetry has been translated into many languages.

1

1