Currently reading

Pluto, Even Closer Up

A remarkable photograph of the surface of Pluto, more than 4.28 thousand million kilometers away from us

As a little follow up on my posting about the fly-by of Pluto by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft, here is a striking photo and a link to an article in the New York Times:

New Horizon is now headed into the Kuiper belt and is still sending back data.

6

6

9

9

On Writing History

Clearly, the historian is not concerned with all men, circumstances and events; he has to pick and choose. And what is his criterion of choice? However warily the answer is formulated, it will trap the mind in a vicious circle. For it is the historian's view of what is historical that determines his selection. The 'historical' facts are singled out from the inarticulate mass of facts that constitute 'the past'. These selected facts must then be recorded in a coherent manner: in words, and with a view to plausible causal connections. Having been unavoidably biased in his selection of facts, either by the socially predominant or by his personal view of what is 'historical', now, at least, the good historian may hope to be 'objective' or 'purely technical'. But by describing in words men, human actions and human motives, he implicitly conveys and evokes emotions and passes moral judgments. If he is wise and subtle, the emotions evoked will be complex, the moral judgments fine and just. Yet they will be there, for they are in the words themselves and in our responses to human behavior.

The goal of objectivity proves still more unattainable as soon as we are faced with the problem of establishing causal connections. For history is, of course, not concerned with physical pulls and pushes, or chemical reactions, which can be reproduced in the laboratory for experimental purposes. The stuff of history is made of unique situations, singular and complex because they are brought about not by scientifically ascertainable cause but by human motives. And however many 'facts' the searching scholar may unearth to support his conclusions, these must finally be reached through the full exercise of his imaginative sympathy. Thus, in every single case, the historical picture is established by the historical imagination, not by scientific reason, and proved not by objective experiment, but by the persuasiveness of the historian's vision. This vision, to be persuasive, must have force; and its force lies in the quality of its order or pattern. In this last respect history is like a work of art, and what has happened in recent historiography has happened time and again in the history of art: a nervous quest for a constant, or a centre, capable of imposing order and pattern on the confusing wealth of sensations and impressions.

- Erich Heller, in The Disinherited Mind

3

3

Poem by Fan Chengda (1126-1193)

Composed Ten Days Before Spring

Spring's almost on us, but we still owe winter ten days;

Busy with paperwork, I regret how quickly life passes.

My poems are too weak to fetch me some snow,

And wine has lost its magic to dispel my sorrows.

Yet the season would never bully a sick man like me;

We scholars just like to gripe about our problems all the time.

Why do we fret and worry so much during the short span we're allotted?

After all that fuss and bother, we end up in a dirt hole anyway!

Translated by J.D. Schmidt in the excellent Stone Lake: The Poetry of Fan Chengda, 1126-1193 (1992).

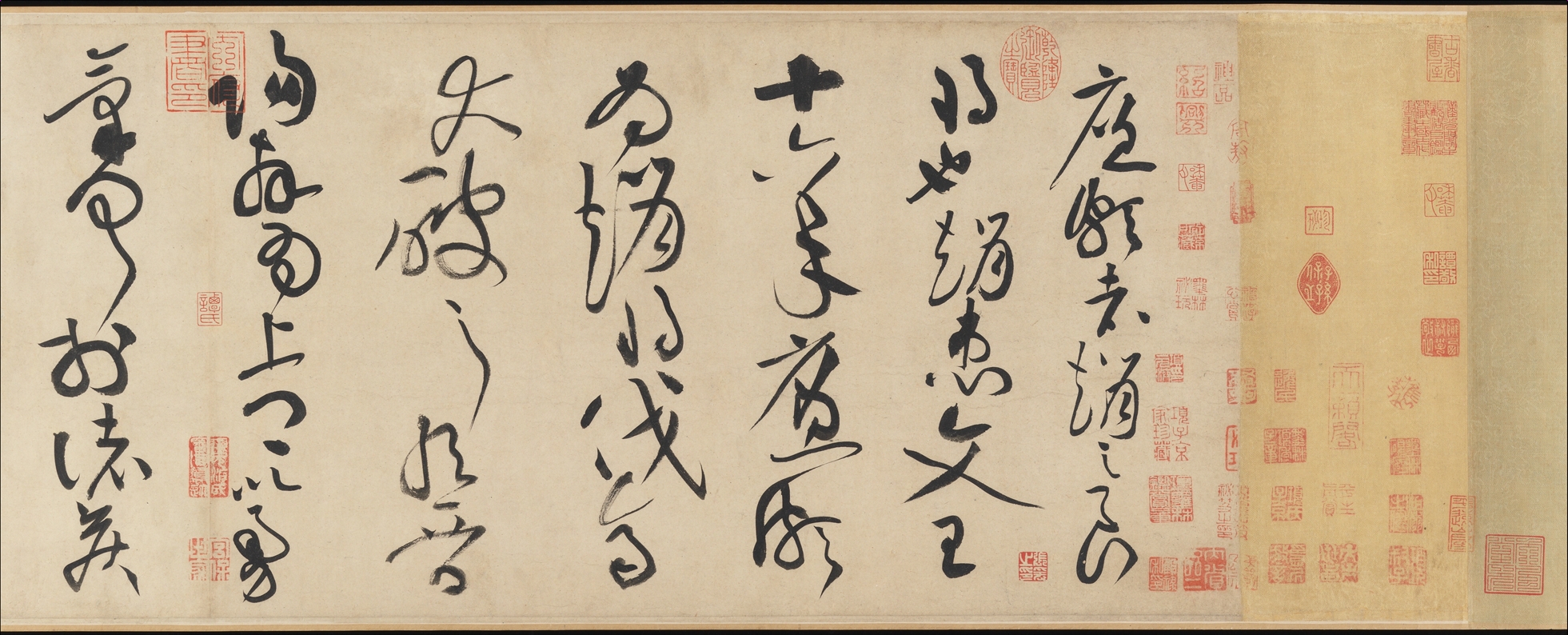

Calligraphy and Poem by Huang Tingjian

Huang Tingjian (1045-1105)

Two Poems on Playing Chess Presented to Ren Gongjian (first poem)

By chance we've no government business and the guests have retired;

We armchair strategists compare our wits in a game of chess.

Our minds are spider webs floating through the empyrean's void,

Our bodies, moulted cicada shells, cast off on a withered branch.

"One-eyed" like the King of Xiandong, we willingly perish in battle;

Our chess "empire" is divided in two, and we can both hold out forever.

Who says that we humans always worry about time's onslaught?

We don't even know that Orion is dipping and the moon set long ago!

(translation by J.D. Schmidt, Stone Lake: The Poetry of Fan Chengda)

The Real Lives of Roman Britain , by Guy de la Bédoyère

1st Century Roman mosaic in the Roman palace at Fishbourne, Chichester

Though Britons in the Southeast had commercial dealings with the Roman Empire and tribal leaders had been displaying their status by bringing prestige items across the Channel for quite some time, they didn't feel the weight of the Empire until Julius Caesar's adventures on the scepter'd isle in the summers of 55 and 54 BCE. But Caesar had other matters on his plate and left, taking his army with him. Subsequent invasions were planned by Augustus and Caligula, but it was Emperor Claudius who sent four legions to occupy the island in 43 CE. The Roman army would remain until approximately the year 410 - the aftereffects of Roman civilization would remain significantly longer.

As Guy de la Bédoyère warns, The Real Lives of Roman Britain (2015) is not a history of Roman Britain, it is a glimpse into what can be retrieved about the lives of the people who lived there and then. Some history is related for context, of course, but the focus is on culture with a small "c" and "normal" life as evidenced by archaeological digs, numismatics, funerary and other inscriptions, the Vindolanda tablets(*) and the like.

For the most part, this is done very soberly. Along with explicitly declining to pass a value judgment on the occupation, de la Bédoyère doesn't choose to tell the most colorful versions of his tales. For example, instead of playing all the registers of the well known story of Boudica as embellished by later fabulists for various purposes, de la Bédoyère explains what little one really can know and what motivated Tacitus and Cassius Dio to set the legend in motion in the first place. So, this is not a popularization of the egregious sort one might be led to expect by the title. (The fact that the book is published by the Yale University Press is also a hint.) On the other hand, it is also no dry-as-dust academic monograph of the sort I have been reading lately (and learning a great deal from). The roughly chronological organizing principle suggested on the level of chapters is constantly violated in the very digressive paragraphs, as is seemingly any other likely form of organization.

Though the famous make their cameo appearances, the author draws our attention to the Thracian trooper, Longinus Sdapeze, who died at forty after fifteen years in the saddle on Rome's behalf - before he had reached the magic number of 25, at which he would have become a Roman citizen; and Saturninus Gabinius, the "most idiosyncratic" of the water nymph Coventina's adherents, who fabricated from clay two curious incense burners and proudly inscribed them with his name; and the Gaulish import/export businessman, Lucius Viducius Placidus, who was so successful that he made a dedication to a local goddess in what is now Holland and paid for a gate and arch in a temple precinct in York; and the Briton, Verecunda, daughter of the Dobunni tribe who married a Romanized Gaul, Excingus, and died at thirty-five to be buried in the Roman manner and marked with a Roman tombstone inscribed in Latin. To mention only a few of many. Although each individual emerges out of the shadows of time only briefly to wave and then recede, de la Bédoyère uses them to exemplify the general facts about ordinary life in Roman Britain that he weaves into the discussion.

And so we have here a Sammelsurrium of the activities, customs and beliefs of Roman Britons, as can yet be reconstructed from their traces. (And what a difference there is between the nature and quantity of the pre-Roman traces and the post-Roman!) One finishes the book with the feeling of having glimpsed the ordinary life of the place and time, something that is generally not vouchsafed to the curious by those who write histories.

Model of the Fishbourne palace, built some 30 years after the Claudian invasion

(*) The Vindolanda tablets consist of correspondence and records written on thin sheets of wood that were found in the ruins of a Roman fort on the northern frontier of Roman Britannia. They provide direct insight into the day to day life of the people living and working there around 100 CE. An Oxford website dedicated to these tablets may be found here:

http://vindolanda.csad.ox.ac.uk

It appears that as a young man the poet Juvenal was posted at Alauna, one of those northernmost forts.

A portion of Hadrian's Wall marking, for a time, the northern frontier of Roman Britannia

Still No Resolution of the Reblogging Problem?

After a much needed three week break from all of the book sites I normally participate in, I return to find that there still is no resolution of the reblogging problem at Booklikes which so many people made noise about in the middle of July. Seven weeks have passed, so I have to wonder if we are witnessing a repeat of the earlier efforts made by active Booklikers to bring the reblogging problems to the attention of the Booklikes honchos, which made no difference at all in the end. Nothing was done then, either. I have seen Booklikers praise the honchos for their responsiveness, but in this matter - the only one that really has any significance for me personally - still nothing has happened. Can one still hope that they will do something about it?

6

6

6

6

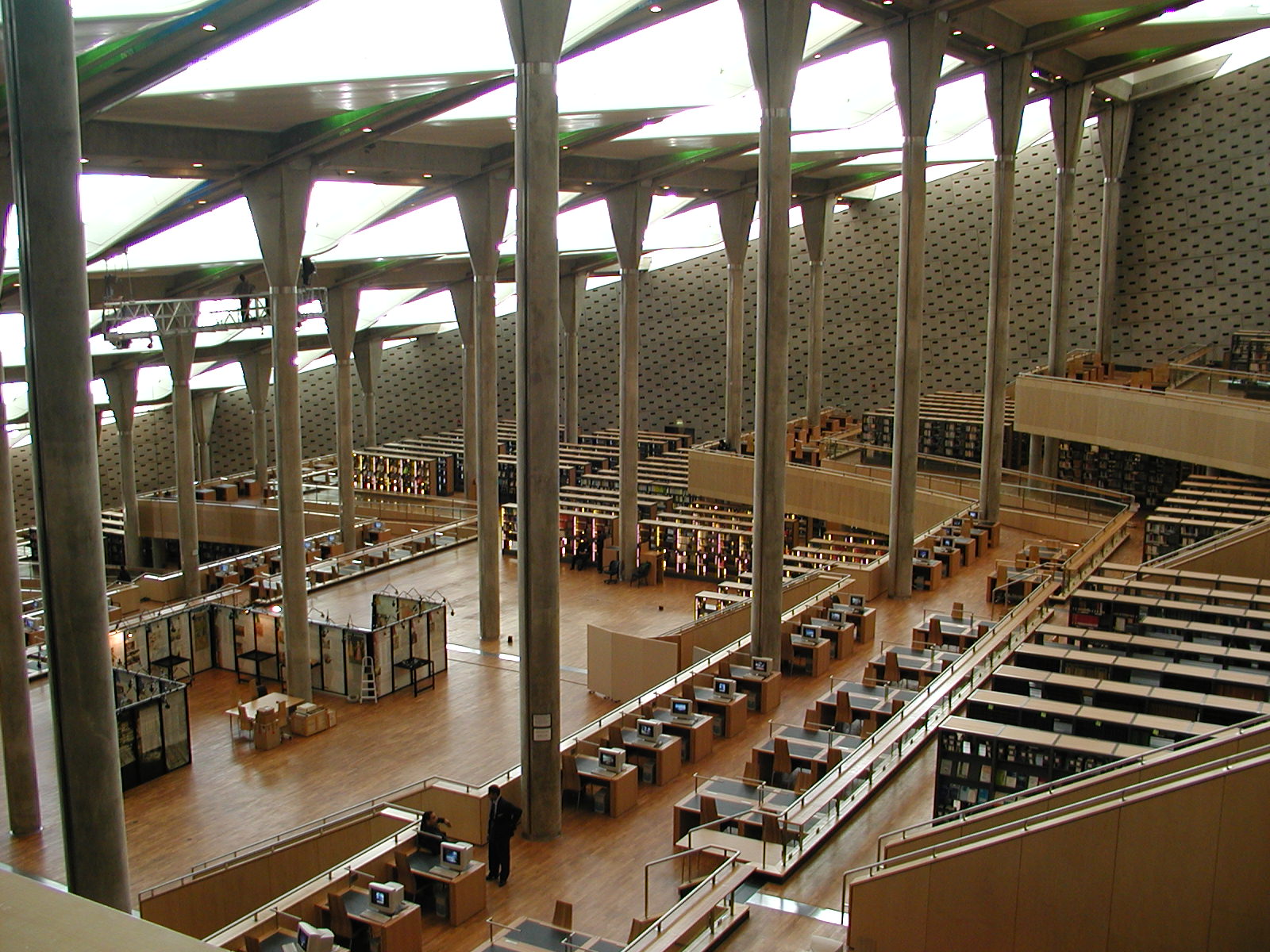

Bibliotheca Alexandrina - Resurrecting the Fabled Library of Alexandria

The Bibliotheca Alexandrina - financed by the Egyptian Ministry of Education, the richer Arab countries and UNESCO, designed by a Norwegian firm and opened in 2002 on the former site of the palaces of the Ptolemies - has a capacity of 8,000,000 volumes and the goal of reviving the spirit of the ancient Library of Alexandria, which was for centuries the most important library and center for research in the Greco-Roman world.

The library's collection is trilingual - Arabic, English, and French - and in 2010 the Bibliothèque Nationale de France donated a half million volumes, making the Bibliotheca Alexandrina the sixth-largest Francophone library in the world.

The monstrous main reading room is, at 70,000 square meters, the largest in the world. I wouldn't want to read there, but I would love to see it. Let's hope this underfunded prestige project succeeds.

1

1

History as a cure for jingoism

There is scarcely any folly or vice more epidemical among the sons of men, than that ridiculous and hurtful vanity by which the people of each country are apt to prefer themselves to those of every other; and to make their own customs, and manners, and opinions, the right and wrong of true and false. ... Now nothing can contribute more to prevent us from being tainted with this vanity, than to accustom ourselves early to contemplate the different nations of the earth in that vast map which history spreads before us, in their rise and their fall, in their barbarous and civilized states, in the likeness and unlikeness of them all to one another, and of each to itself. ... I might shew, by a multitude of other examples, how history prepares us for experience, and guides us in it: and many of these would be both curious and important. I might likewise bring several other instances, wherein history serves to purge the mind of those national partialities and prejudices that we are apt to contract in our education, and that experience for the most part rather confirms than removes, because it is for the most part confined, like our education.

- from Letters on the Use and Study of History (1735) by Henry St. John Bolingbroke (1678-1751)

5

5

4

4

Pluto, Close up

A closeup of Pluto recently taken by NASA's New Horizons spacecraft, which has just done a fly by within 7,800 miles past the most distant (former) planet of our solar system. Since this probe has measured Pluto to be larger than previously believed, perhaps poor Pluto will be promoted back to the status of planet...? New Horizons is now on the way to deep, deep space after one hell of a trip:

5

5

So long Booklikes

Yesterday I posted a review of James Tate's Absences in honor of his passing on Wednesday. Debbie Spurts reblogged the post without asking, but I sat and watched, thinking that perhaps one of her readers would click through her reblog to "like" the original post, or even follow the author of a "liked" post. Well, that didn't happen at all. The reblog got 13 "likes" and the original 3... :)

That didn't bother me much, but I noticed that as I made modifications to my post, they weren't reflected in the reblog. I went so far to run an experiment: I deleted my original post (I still have the last draft) and the only change in the reblog was to no longer signify that it was a reblog!

After a few requests Debbie Spurts was kind enough to delete the reblog, and I thank her again for that. But this is my last post on BL. I will keep my account because I love two things about BL: (1) The format of the posts is much nicer than the format at GR and Leafmarks; (2) The draft feature is wonderful.

So I will continue to draft any reviews I may write in the future here, but will only post them in GR and LM, who do not have such a reblog feature. Perhaps we will run across each other in those sites. In any case, take care folks!

7

7

30

30

The Life of Forms in Art , by Henri Focillon

Early Gothic figure from the cathedral at Naumburg

Henri Focillon (1881-1943) was an art historian of great repute and professor at the Sorbonne and later at the Collège de France. He died in the USA while teaching at Yale and working for the cause of Free France, then under the Nazi heel. Of his many books I was first attracted to his Vie des formes (1934),(*) which is a summary of his theory of art. A formalist, he is rather (poetically) abstract in this short text, since he is concerned primarily with the evolution of the morphology of art,(**) but I would like to summarize the aspects of the book that drew me to it in the first place.

In Vie des formes Focillon presents a typology of the evolution of style in art, wherein he proposes that every art form progresses through four stages(***) which he calls Experimental, Classical, Refined and Baroque. In the Experimental stage (which he also refers to as Archaic) a nascent style is casting about for its (often tacit) principles in order to define itself and is therefore experimenting with not always happy results. In the Classical stage the style has decided upon its principles and is, in a stable and secure manner, working out their consequences in concrete works. It is not yet manifesting conformism or academicism. In the stage of Refinement the style develops in the direction of increased elegance and often lands in a state of dry purity. In the Baroque stage, which Focillon asserts is "without doubt the most liberated", the principles of the style are taken to extremes that become their own ends and exhaust all the creative impulse of the style. Then one must recommence from a new beginning, a new stage of Experiment.

3

3

Scipio Africanus, Greater Than Napoleon , by B.H. Liddel Hart

Publius Cornelius Scipio (236–183 BC)

Publius Cornelius Scipio, better known to history as Scipio Africanus (the Elder), was very likely the greatest general the Roman Empire ever had, entering the written record at the age of seventeen when he led a cavalry charge that saved his father's life (the commander of the Roman forces) at the battle of Ticinus, the initial encounter of Hannibal's forces with the Roman army on Italian soil. The Romans lost that battle and almost all of the subsequent battles until Scipio was elected commander of the Roman forces in Spain at the age of twenty-four. Scipio Africanus: Greater Than Napoleon (1926) is an account of Scipio's life with an interesting twist.

Basil Henry Liddell Hart (1895–1970) was a soldier and military theorist and historian who in the 1920's and 30's urged upon the British military establishment a reliance on the air force and navy that relegated to the army a secondary role in which the armored branch was pivotal. In ground actions he argued against direct attacks on well-made defensive positions, preferring what he called the Indirect Approach.

What gives Liddell Hart's Scipio Africanus additional interest above and beyond his careful use and extensive quotation of the Roman sources(*) is that he uses Scipio's strategies and tactics to illustrate his idea of the Indirect Approach, which may be suggested briefly with "Those who exalt the main armed forces of the enemy as the primary objective are apt to lose sight of the fact that the destruction of these is only a means to the end, which is the subjugation of the hostile will." He does not do so overbearingly, for the text is certainly focused on Scipio's career, but again and again he points up what he views as lessons for (then) modern warfare.(**)

6

6

6

6

The New Oresteia , by Yiannis Ritsos

Yiannis Ritsos (1909-1990)

A significant portion of the poet Yiannis Ritsos' (Γιάννης Ρίτσος) prolific output was intended, at least in principle, for the stage. And of this portion, the dramatic monologues are reputed to dominate artistically. The New Oresteia of Yannis Ritsos (1991) is a translation of those monologues that involve Agamemnon's legendary family.

Ritsos took up this task partly because he felt a certain affinity with that family, an affinity that makes itself strongly felt in these monologues. Born into an aristocratic family that fell onto hard times after the 1909 revolt, his elder brother and his mother died of tuberculosis within three months of each other when he was twelve years old (he himself suffered from the disease). Both his father and his sister died in an insane asylum. So, though there were no murders and feasting upon relatives in his own family, Ritsos knew familial loss and tragedy from the inside out.

3

3

The Oresteia , by Aeschylus

Let good prevail ! So be it ! Yet what is good ? And who is God?

As many deeply conservative societies have discovered time and time again - societies in which there is only one right order and this order is warranted by the highest authorities recognized by the society - when change comes, and come it always must,(*) not only do those in power tumble, but the authority of the gods/priests, ancestors, laws, whatever the highest authorities happen to be in that society, comes into question. New myths, new gods/priests, new stories must be told to justify and establish, reassure and mollify the people whose ideological or religious supports have been pulled out from beneath them. In the city of Athens during the Golden Age, this was done in the agora - the marketplace - and in the theaters.

In his lifetime Aeschylus (ca. 525 - 456 BCE) witnessed the invasion of Attica by huge Persian armies, the bold abandonment of the fortified city of Athens and withdrawal, twice, of the Athenian people behind the wooden walls of the Athenian navy, and the multiple defeats of the Persians and their allies (including other Greeks) by the hugely outnumbered Athenians and their Greek allies.(**) He also witnessed the political transition from tyranny to isonomy to democracy in Athens and the concurrent growth of Athens from just another small, unimportant Greek city-state to major power. He himself contributed greatly to the transition of Greek tragedy from a religiously inspired performance/rite involving a chorus and a single actor to something we his distant descendants can recognize as powerful theater.

3

3

The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology , by Edmund Husserl

A philosopher's desperate play for relevance in 1935/36.

Edmund Husserl (1859-1938) is regarded as the founder of (philosophical) phenomenology, an extremely influential development of modern philosophy which tries to capture the nature of the Subject through a combination of close description and transcendental theorizing.

The word "phenomenology" literally means the study of phenomena. When an elementary particle physicist speaks of phenomenology, what he refers to is a description of the experimentally observed behavior of elementary particles, already (necessarily) partially interpreted - for example, "when a proton collides with an antiproton, then this, this and this happens" - but without a thorough theoretical "explanation." The word is in use in a number of fields, including philosophy, though the resemblance of the various flavors of phenomenology is often hard to make out. Compare, for example, the physicist's phenomenology with Husserl's, for whom phenomenology was “the science of the essence of consciousness.” But all of them try to provide as minimally a theory laden description of "reality" as possible, at least in principle.

The phenomenologist reveals himself in his choice of fundamental phenomenon - in the near infinitude of phenomena, where does he focus his eye first, which is the key he uses to unlock the door of "reality"? Since it is our own conscious sensations to which we have the most direct access with the least amount of adduced concepts, in an attempt to strip away from "reality" the thick veneer of conceptualization, the many layers of intervening concepts and modes of regarding "reality" which have been built up over the ages by human beings trying to understand that "reality" and then to try to recognize "reality" for what it "really is," the focus of the philosophical phenomenologist is on various aspects of experienced consciousness in relation to that which is outside that consciousness. That, too, is a vast expanse.

5

5

The Huns , by E.A. Thompson

Anthony Quinn as Attila wearing surely the most absurd helmet in the history of cheapo film productions.

The nation of the Huns, scarcely known to ancient documents, dwelt beyond the Maeotic marshes beside the frozen ocean, and surpassed every extreme of ferocity.

- Ammianus Marcellinus

Attila the Hun! Is there any name more evocative of barbarian hordes looting, burning and murdering their way through civilization except possibly Genghis Khan's?

In the final, thirty-first book of Ammianus Marcellinus' magnificent history of the late Roman Empire is to be found the earliest extant source on the customs of the Turkic nomads called the Huns. Since the Huns were little more than bogey men to me, I thought it was time to see what one knows about them.

4

4